Upon assessing the year-end economic situation, one continues to find a two-faced economy. One face, the one reflecting inflation, supply bottlenecks, and GDP growth, is unsmiling and, at times, even frowning. Yes, as measured by the all-item monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI), the overall price level grew at 7.7 percent in October, slightly less than the 8.2 percent registered in September, but far above the 2.0 percent inflation target of the Federal Reserve (Fed). When stripped of food and energy, the October index continued apace at a 6.3 percent annual rate.

Thus far, stalwart efforts by the Fed to control inflation, which began in March 2022, are not showing up in monthly CPI readings or in the Fed’s preferred measure, the Personal Consumption Expenditures index, which is released by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. The index annual growth rate for September was 6.2 percent, the same as for August. Unfortunately, COVID-19 and the Russo-Ukrainian War have generated bottlenecks, and supply disruptions are still present. And even with the third quarter’s 2.9 percent growth in real GDP, which was driven heavily by petroleum product exports to Europe, hardly anyone will be popping corks to celebrate.

When the second quarter’s −1.6 percent growth and the first quarter’s −0.6 percent growth are

accounted for, and if one assumes the fourth quarter’s growth will be slightly positive, growth for the year is still likely to be less than 2.0 percent. Forecasters see an even weaker 2023 ahead. For example, Wells Fargo is calling for −0.1 percent growth for 2023, and the Wall Street Journal looks to see 0.4 percent real GDP growth.

Yet while the Fed’s tightening has had little effect on inflation so far, the associated interest rate run-up has created serious challenges in credit and exchange markets. The yield on 10-year Treasury notes rose from 2.48 percent on March 25 to 3.67 percent on November 16. As a result, housing and related construction activity have taken it on the chin, and the relative value of the dollar has risen significantly. Global trade patterns have been seriously disturbed, as has the ability of debtor nations that pay with dollars to cover their debt payments. Some of these tensions are beginning to ease as the European Central Bank and the Bank of England raise interest rates to levels similar to those in United States.

Looking for a Happy Face but Finding Three Bears Instead

But what about the economy’s happy face? Armed with large increases in personal wealth generated by pandemic stimulus money and debt forgiveness, American consumers are still spending, particularly on services. Although home purchases and construction starts have slowed significantly, the consumer is neither down nor out. Along with healthy consumer spending one finds a strong employment picture. Although the employment level is high and unemployment rate is low, the pace of job openings is slowing.

Yes, when the Fed puts its foot on brake, the economy eventually responds, which is, of course, the point. This said, one should recognize that the number of coins in the consumer’s piggy bank will eventually diminish; all else the same, consumption expenditures will fall, and the unemployment rate will tick up. As indicated earlier, one should look for that to happen in 2023.

What about Goldilocks?

Even with aggressive Fed tightening and the high volatility seen in equity markets, along with other global uncertainties, there are still a few brave souls who suggest the economy may avoid a hard landing as this slow-down occurs and once again who see a Goldilocks economy where everything is just right. Those happy days when everything economic seemed just right, and where inflation and GDP growth were neither too hot nor too cold are over for a while. Unfortunately, just as the storyteller reminded us, the three bears came home and scared the hell out of Goldilocks. She is nowhere to be found.

What are those three bears that chased away America’s happier times? And when might they go back to the woods so that Goldilocks can find peace and happiness again?

The first bear is the pandemic. Yes, Americans are no longer told about COVID-19 disasters on a daily basis, but they still cannot find a wide selection of new cars on dealer lots, there is a short supply of entry-level workers, there are lots of people who left the labor force and have not returned, and the healthcare system—particularly hospitals—is still strained. Even worse, because the last folks to return to work are typically less experienced, worker productivity is likely in decline, and that might slow down the growth rate of GDP.

Richard Grant called the US economy the Incredible Bread Machine, and this machine is still bent out of shape. It may recover in 2023, but thinking that way may be nothing more than wishful thinking.

The second bear is the Russo-Ukrainian War and related disruptions in energy markets. Within the news coverage of the horrors of the invasion, not much attention has been given to the destruction of human and physical capital. There are no reliable data on the number of lost lives or the number of destroyed man-made structures in this war, but one can be sure that each day that hostilities continue, the world is made poorer.

And yes, people worldwide can feel the pain of high electricity and gas bills. One can surely expect the energy crisis component of the war to continue. This second bear will be here until long after the Ukraine invasion has ended.

The third bear, as one may guess, is inflation coupled with the Fed’s obligatory effort to bring it down. In a way, it seems strange to suggest that Goldilocks is gone, because the Fed has had its own trouble deciding when the economy is too hot or too cold. In a real sense, it’s strange that the comptroller of the nation’s money supply seldom if ever talks about money and its supply when describing the forces that beset the nation and what might be done about them. Instead, one hears constantly about interest rates, supply chain problems, and energy supply. And while that chatter fills the evening news, investors and other ordinary Americans are left to guess just what might happen at the next Fed meeting. Guessing means uncertainty, and uncertainty means falling investment and delays in building the new modern economy.

How This Report Is Organized

The remaining parts of the report are organized as follows. The next section looks more closely at the relationship between the supply of money in the economy, job openings, and employment. Efforts by the Fed to reduce the money supply are seen in data reported in this section. As seen here, in recent months, growth in job openings has been slowing down while employment growth continues apace. The section also addresses the severe challenge the Fed faces owing to the political calendar and midterm elections. Officials on one side of Washington DC are hitting the brakes while those on the other side are hitting the accelerator.

The following section brings a discussion of consumer wealth and how families across the income spectrum are financially fortified to continue spending.

With a change of focus from the national economy, the next section addresses the pressing water supply crisis faced by people living in the US southwestern states as the diminishing flows of the Colorado River become unable to satisfy the current demand for water. The section discusses institutional change that might be considered for bringing supply and demand into balance.

The report then puts the spotlight on regulation by the director of the Mercatus Center’s Policy Analytics project, Patrick McLaughlin, who gives a report card on the Biden administration’s regulatory activities. The report ends with a couple of book reviews from Yandle’s reading table.

Money, Job Openings, and Employment

Efforts by the Fed to slow the economy depend on the effects of interest rate increases on the money supply as conveyed through credit markets. For example, when the aggregate level of demand deposits goes down, the pace of economic activity slows, and eventually, so will the rate of inflation. At least, that is the theory. Recent news that US bank deposits have fallen for the first time since 2018 is indirect news that the Fed’s effort to slow the economy is working. From the Fed’s standpoint, a slowdown in money growth, which includes the demand deposits now in decline, is a necessary first step in reducing economic activity and, perhaps, reducing inflation. But the latest reading on the CPI, which shows that October’s all-item number rose by 7.7 percent year-over-year (nearly mirroring September’s 8.2 percent but below August’s 8.3 percent), shows that the effort to hammer down inflation will not be easy.

Given inflation’s stubborn hold, employment, the mainspring of US personal income, is now the major concern. Will the Fed’s continued cut in money supply growth take the edge off employment before taking down inflation? This is the question.

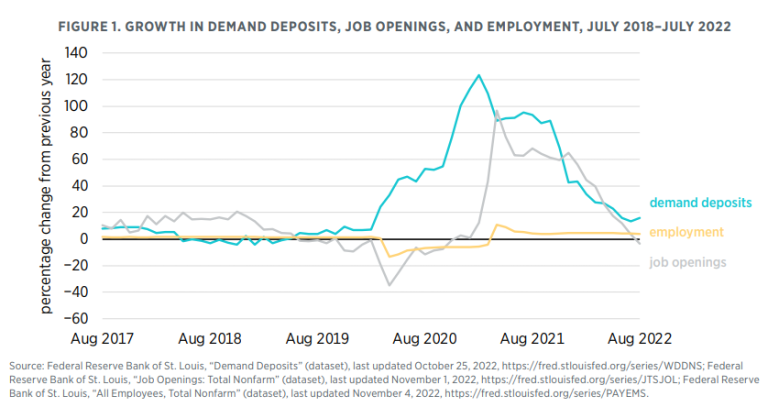

A quick look at year-over-year growth for demand deposits, job openings, and employment for the past five years sheds some light on the matter (see figure 1).

First off, consider demand deposits, the money side of the matter. The figure reveals the explosive growth that occurred from 2020 through early 2022, when presidents Donald Trump and Joe Biden showered the economy with stimulus money. Note that year-over-year growth exceeded 120 percent in early 2021. This provided fuel for inflation that would come later.

But what about job growth? Did printing money bring about jobs? The figure shows that job openings exploded and that this explosion lagged the growth in demand deposits by several months. (After all, it takes a while for businesspeople to recognize that demand for goods and services is increasing and to demand more themselves.)

But job openings are not the same thing as jobs. For job growth to occur, unemployed people—including in some cases those receiving generous government aid—have to show up and fill the jobs. Did that happen?

It did not. Yes, there was some mild gain in job growth, but it was nothing compared with the gain in job openings.

One can think of this figure as an abstract view of the “now hiring” signs Americans all see when shopping. It also helps to explain why being placed on hold when calling the pharmacy, bank, or restaurant seems to be more common. Yes, the world seems to be understaffed. There are lots of openings but no scramble in labor markets to get them filled.

The figure shows that, getting closer to the present, demand deposit growth has indeed plummeted. Yes, the Fed is at work trying to cool off the economy. The figure also shows that job openings growth is headed to the basement. Yes, private employers are getting the message. And finally, the figures shows that growth in employment has held steady.

So, what does this portend for the future? It is possible that the decline in job openings—the thing the economy has at its disposal but failed to use—is the big shock absorber that cushions the economy from severe recession while the Fed continues to hit the brakes. And given the lag between changes in growth in demand deposits and changes in job openings, one might look to 2023’s last quarter to see the tougher employment effects of the effort to wring out inflation. This projects to be when job openings are no longer growing and employment growth is at zero or less.

Meanwhile, keep your trays in a locked, upright position. There are some storm clouds on the horizon.

The Fed’s Lonely Battle

Though apparently dedicated to winning the battle against inflation, Fed Chair Jerome Powell is fighting a lonely battle that will be difficult to win, at least with an election taking place. There are limits to what the Fed can do when Congress and the White House are busy printing more money. Yes, even after a six-month Fed effort to raise interest rates, US inflation is still running at a hot 7.7 percent.

It will take time and restraint from Washington before things have a chance to calm down. Because inflation’s causes lie in politics as much as economics, one may look past election-dominated 2022 for possible relief. There are some early data to support this hope.

For all the talk about the what’s behind the diminishing buying power of Americans’ money—war, supply chains, energy prices—inflation can still be thought of simply: flood the economy with enough money and the money will start to lose its value. That’s how White House and congressional efforts to forgive debt and increase spending have been countering the Fed’s action.

In just the past six months, the Biden administration has initiated massive student debt write-offs, forgiven billions of dollars of farmer-owed debt, and assisted drought-distressed people in the Southwest by way of the misnamed Inflation Reduction Act. (It is worth noting that the Wharton School’s dispassionate review of the act found the effect on inflation to be “indistinguishable from zero.”)

Whatever one thinks of these policies, they mean that while the Fed is hitting the brakes, the White House—perhaps fearful of what the midterm elections would bring—was goosing the accelerator. And Heaven help us to get past efforts by Democrats and Republicans alike to score political wins with their constituents and secure majority positions in the House and Senate. Now that midterm “crazy season” is over, it’s clearly possible that some of the inflation heat may subside.

One can also see data backing this up. Inflation, as reflected by the CPI, could approach a healthier 2 percent again late in 2023. Hope comes from examining another measurement, M2, which tracks the US money supply by accounting for US cash, deposit assets, and other near-money accounts.

The money supply exploded in early 2020 with COVID-19 relief spending; CPI-registered inflation accelerated about 12 months later. It was a textbook case of too much money chasing too few goods. Now the latest M2 reading is back at a pre-COVID level. That suggests more normal inflation levels about 12 months from now.

Of course, some of those other inflation factors must still be noted. There is always more to the story, including Russo Ukrainian War–driven energy price increases, supply chain disruptions, and labor market challenges that emerged during the pandemic and remain to be dealt with.

It is for this reason that some are suggesting the Fed should be happy with 4 percent inflation rather than 2 percent. After all—this thinking goes—living with a little more inflation might be preferable to sustaining the bitter medicine of an economy slowed down by the Fed. But it’s also possible that war-caused disruptions in energy markets and other markets will eventually disappear, making the job of hitting the ideal target easier (though by no means painless).

Yes, one can be optimistic that inflation will be under control in 2023—that is, if the Fed is not forced to hit the brakes harder to offset an election-year spending binge. One just hopes Congress will not be inspired to write another so-called Inflation Reduction Act any time soon.

Cash-Rich Americans and the Rolling Economy

The Fed’s encouraging September report on US household wealth must have brought comfort to those concerned about the ability of American families to deal with the Fed’s effort to corral inflation and with the slowing economy that may follow. The report indicates consumers are sitting on a lot of wealth including cash. But at the same time the magnitude of asset growth reported suggests the Fed’s effort to reduce economic activity by raising interest rates will be far more challenging than might be the case otherwise.

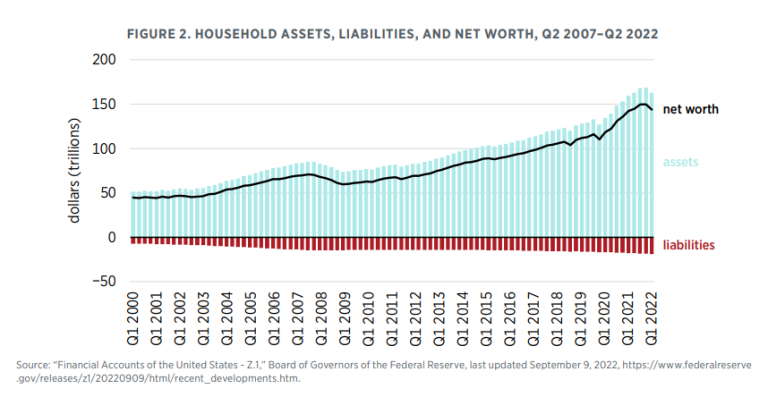

Figure 2, which is taken from the Fed report and covers Q2 2007 through Q2 2022, shows how the level of household assets and net worth accelerated in 2020 and peaked in Q4 2021 as stimulus checks made their way into consumer bank accounts. Of all asset categories, real estate and cash saw the most significant rise in value along the way while the stocks and bonds lost value in the most recent period.

A few segments of American society are sitting on substantial wealth and cash, and this is not just the case of wealthy households. An analysis of the Fed data by Wells Fargo indicates that “cash assets of the bottom half of the population by wealth are 49% higher compared to the end of 2019, while the top 1% have seen a 54% gain, indicating a consistent rise in cash since the end of 2019." Comparing the level of prepandemic savings with what has happened since 2020, Wells Fargo estimates current excess savings to be $1.3 trillion dollars. I note that total retail sales for the US economy in 2021 were $6.6 trillion. Put another way, US consumers have a substantial savings shock absorber that can keep them shopping into 2023, in spite of higher Fed-delivered interest rates and the effort to slow the economy.

Of course, all eyes are on the Fed in this current struggle with inflation. After all, inflation is a monetary phenomenon. But efforts by the Fed to raise interest rates to the point that the economy and employment growth slow places all the focus on the demand side of the economy. But if excess-savings-fortified demand keeps consumers buying in spite of higher interest rates, perhaps the policymaking spotlight should be turned on the economy’s supply side as well.

What might Washington policymakers do to free up the supply side so that the economy may deliver more goods at the same level of demand and thereby bring down inflation? First off, tariffs, quotas, and other trade barriers imposed in the past should be targeted for removal. For example, tariffs on Chinese goods that emerged during the Trump administration should be hung out to dry along with other actions limiting the flow of lower-cost goods to American consumers.

Then, more attention should be devoted to the work of the White House Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) that attempts to reduce the burden of executive branch regulatory activity. OIRA should make an effort to either suspend burdensome regulations or at least replace them with cost-effective alternatives. Likewise, antitrust authorities should more accurately estimate cost savings in proposed vertical mergers, given that these mergers boost production, streamline supply chains, and accelerate delivery of goods to consumers. Cost-saving vertical mergers tend to produce positive net gains more often than do horizontal mergers, which join one competitor with another and may reduce the efficiencies of competition.

When it comes to fixing an inflation-troubled economy, one needs to remember that there are two sides to the economy. While the Fed focuses on affecting the demand side, other Washington policymakers should set their sights on the economy’s supply side. All policymakers should be held accountable for delivering an easier ending to inflation while also preserving the assets of American consumers.

What about the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022?

This past August, the US Senate passed the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) and by doing so brought to fruition a major Biden administration effort to obtain legislation confronting climate change, healthcare costs, clean (and not-so-clean) energy development, minimum corporate income taxes, and taxes on financial transactions engaged in by some of America’s wealthiest firms and individuals. By any measure—more than 700 pages and more than $700 billion in authorized spending—and by reach of implied federal action, the IRA is a major legislative action.

But consider the act’s title. What about inflation? Does the statute deliver the goods implied by its name? Or is the politically useful title a case of deceptive and misleading advertising? If so, should the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) get involved in the name of consumer protection or, as the case may be, voter protection?

Well, come on. Of course not. The FTC polices the private marketplace, not politics. Still, one can consider what might happen if Americans held their lawmakers to a similar standard and FTC enforcement entered the picture.

Interestingly enough, the Biden administration tends to change the subject when asked to measure the inflation reduction that may be generated by the IRA. Indeed, when pushed during an August 8 NPR interview to talk about inflation, Brian Deese, director of the Biden administration’s National Economic Council, brushed against the matter but spoke more fully about how the new law would cap the annual cost of individuals’ prescriptions at $2,000, provide subsidies for the purchase of electric automobiles, and empower Medicare to bargain with pharmaceutical companies so as to hammer down drug costs.

Deese’s response was not about inflation—what happens to all prices taken together—but about the relative prices of some important items purchased by consumers. His comments followed almost to the word the administration’s August 6 description of the legislation: “This legislation would lower health care, prescription drug, and energy costs, invest in energy security, and make our tax code fairer—all while fighting inflation and reducing the deficit.” The wording suggests inflation is almost a side effect.

An analysis of the two most exhaustive treatments of the matter, one by the Congressional Budget Office and the other by the Penn Wharton Budget Model at the University of Pennsylvania, indicates there is no forthcoming inflation reduction generated by the misnamed law. The Penn Wharton Budget Model summary indicated, “the impact on inflation is statistically indistinguishable from zero for either estimate.”

The administration’s reluctance to talk about inflation reduction is perfectly understandable from a political standpoint, even if the statute’s title seems to be patently false.

It seems to me that America’s political leaders should be expected to substantiate their claims. Yes, telling the truth should matter, even in political markets.

Helping Drought-Stricken Colorado River Water Users

Biden administration plans to pay water users in the drought-stricken Colorado basin to cut back their consumption of the sharply diminished Colorado River flow will undoubtedly help the affected users deal with the immediate challenges they face in adjusting to intense water scarcity. But will the payments bring about institutional changes necessary for longer-term adjusted water use that will promote water flow recovery in the years ahead? Or will this payoff need to be repeated again and again in the future?

The White House indicates that $4 billion designated for drought relief in the IRA will be allocated to water users in Arizona, California, and Nevada. In a program managed by the US Department of the Interior, the funds allocated will compensate for a 30 percent reduction in water use, which amount to some 2.4 million acre-feet of water annually. This presumably will enable Lake Mead to recover and bring about a better balance between the demand and supply of in-stream flows.

But the issue of sustainable long-term changes versus short-term fixes was raised by Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Tom Buschatzke when he warned against giving too much attention to compensating current water supply stakeholders instead of changing water management institutions so that future water supply emergencies would be avoided. As he put it, “we can’t pay people forever to do this. It’s not a sustainable process to pay people forever for reductions.”

It would also seem highly doubtful that US taxpayers in the more verdant regions of the country would even consider making such an ongoing commitment. After all, someone has to put money in the till when drought-stricken ranchers and thirsty city dwellers are compensated for their water consumption hardships. These are not pennies from heaven.

The White House program has strong political winds pushing it forward, but dealing with emergency situations that may exist now is a good time to take a longer-term look at the fundamental problem being addressed. The people in the affected Colorado River states have a fragmented system of water use regulations that are focused on cities, water districts, and state water needs. There are no all-encompassing river basin rules or institutions. But the hydrological system to be addressed knows no political boundaries.

Fortunately, there are past lessons to consider. People facing similar water scarcity situations have managed to turn what seemed to be perpetual crises where no one was winning into situations not unlike those Americans use to manage other scarce resources such as land, labor, and capital.

Consider the Ruhr River Basin in the late 19th century. At the time, the river passed through the world’s most heavily industrialized region, an area centered on Essen in East Prussia. Production of coal, steel, and chemicals predominated. Population growth had exploded. Heavy industrial discharge and periods of drought and low river flows created water shortages and typhoid epidemics. Industrial and community leaders decided to do something about it. In 1899 they formed a reservoir association, and in 1913 they incorporated the river and formed the Ruhrverband, a river basin association empowered to manage all aspects of river use.

In effect, the new association became the owner. It first added dams and reservoirs to ease the low flow situation. It then established prices for any withdrawal from the river, whether for drinking or industrial purposes. It set prices for discharges into the river on the basis of chemical and biological characteristics. The revenues were used to improve the river basin. Discharges known to be harmful to fish and other water life were not allowed at any price. In time flows became more dependable, and the river and the land nearby became more valuable assets instead of worrisome liabilities.

The king of Prussia then encouraged the incorporation of other rivers. Competing river basin associations charged prices for their own water withdrawal and use. Competition among the river managers led to water quality innovations that lowered the cost of improvements and increased the supply of water for all users. Typhoid problems ended.

Water from the Colorado River is too precious to treat as a common-access resource where those who get there first get first dibs, or where rigid command-and-control rules for sharing can’t keep up with a diminished flow and burgeoning population. If cutbacks from the current allocations are to be made, why not allow current users to either reduce water consumption themselves or pay another water user to reduce an offsetting amount? The multistate Colorado River basin forms a hydrological unit. It is high time to form a corresponding political-administrative unit that will introduce incentives that ensure that water goes where its value is highest. Lessons from the past may help to improve the situation and make scarcity a prelude to plenty.

A congressionally approved river basin association is needed that encompasses the affected political units and the Colorado River waters. The association could be empowered to buy water use reductions using revenues obtained from water withdrawal permits and be charged with the responsibility of improving water storage and flows. Once the river basin association is established, White House and other politicians could focus their attention on other pressing problems while water use markets managed by the association mediate the Colorado River water-flow problems.

RegData Regulatory Spotlight: Regulatory Accumulation

Patrick A. McLaughlin

Director, Policy Analytics Project, Mercatus Center at George Mason University

Readers of this report are keenly aware that economic growth has slowed substantially and is likely to remain depressed for some time. The Fed remains in difficult situation, raising interest rates to attempt to deal with persistent inflation but simultaneously risking tipping the economy into a prolonged recession. Is there anything the White House or Congress can do to counteract the looming economic slowdown? Or, if Washington fails to take any actions, can state governments or even municipalities do anything to help out?

Indeed, there is, and they can. Recent research has shown that regulatory accumulation (for a slightly amusing visualization of regulatory accumulation, watch me stack up the US Code of Federal Regulations in a video. (Perhaps incredibly, I did not sustain any injuries while making the video.) The buildup of regulations over time can dramatically hamper economic growth. The logic is fairly intuitive: as red tape piles up, it becomes harder for entrepreneurs to innovate, and innovation is ultimately the primary driver of growth in the long term. But the converse is also true: when a country or subnational jurisdiction (e.g., a state or a province) removes a substantial amount of red tape that has piled up over the years, the economy’s growth rate can increase quite a bit. The bottom line is that if a country a state can shed regulations that are obsolete, unnecessary, ineffective, or otherwise undesirable and then keep the total volume of regulations from increasing again, the economy will receive a nice boost to the growth rate.

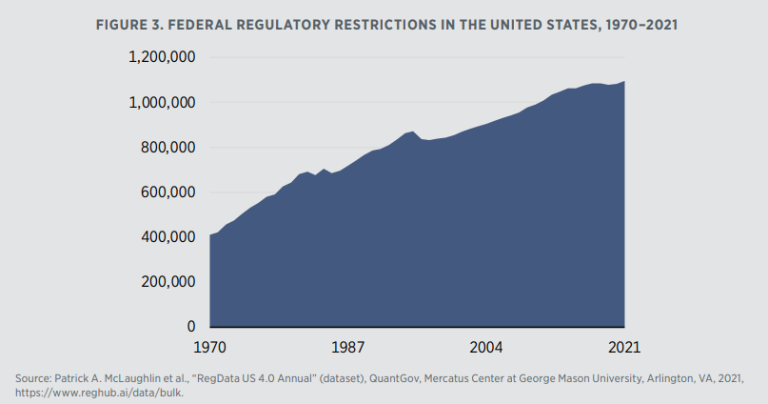

How much regulation is there in the United States? It depends on the location. Federal regulations apply across the country, but state and local regulations differ tremendously. First consider federal regulations. Figure 3 shows the accumulation of regulations at the federal level from 1970 to today. The data come from RegData, a dataset available at QuantGov.org. One of the primary metrics in RegData is regulatory restrictions—i.e., words and phrases that are likely to create either an obligation or a prohibition. These are words such as “shall,” “must,” and “may not.”

The growth of regulatory restrictions over time is remarkable, going from about 400,000 restrictions on the books in 1970 to nearly 1.1 million on the books as of 2021. Although there were a few years in the 1980s and 1990s when the count of regulatory restrictions decreased, the big picture is one of consistent regulatory accumulation. The slope is more or less constant—somewhat steeper in the 1970s, when many of the social regulatory agencies were first created, and somewhat slower in the Trump years; but otherwise one would be hard-pressed to say that the trend is anything but positive and linear.

But my focus is not the rate at which regulations grow. Instead, it is the fact that there are a lot of regulations. That simple fact simultaneously presents an obstacle to faster economic growth and an opportunity for policymakers to counteract a potential recession. The opportunity comes, at least in part, by learning what policymakers from the west coast of Canada did to cut back on their own regulatory accumulation. In 2001, the province of British Columbia began implementing a regulatory budget—a simple system of monitoring how much regulation there was and using quantitative metrics to track progress towards cutting the total amount by a targeted amount. The goal was to cut regulations by one-third, but in fact the province cut regulations by 40 percent within three years. In a study I did in 2021 with Bentley Coffey of the University of South Carolina, we find that by cutting red tape by such a large amount so quickly, British Columbia’s regulatory reform effort directly caused the economic growth rate to increase by about 1 percentage point:

"By adding new rules and restrictions on top of existing ones, the negative effects on the economy of regulatory accumulation are compounded. Such accumulation can occur in subnational (e.g., state, provincial, or municipal) and supranational (e.g., the European Union) settings as well as in national jurisdictions (e.g., US federal regulations)."

"To date, however, very few governments have launched successful interventions. This makes British Columbia’s regulatory budgeting experiment all the more extraordinary. Regulatory budgeting, at least in the way that British Columbia implemented it, offers policymakers a very effective path to increasing economic growth without having to increase fiscal outlays."

The message today remains the same. The federal government has not successfully halted the continual accumulation of regulations, and there is surely a boatload of old rules on the books that are causing more harm than good. Regulatory budgeting implements the old adage “what gets measured, gets managed.” If the powers that be in Washington want to explore ways to counteract the effect of raising interest rates, they should explore implementing a regulatory budget. Start by measuring how much regulation there is and how much is being created. Then set a target: reduce by some percentage, or allow growth of only some percentage. Various options for how to measure regulations exist, and many have been explored and implemented by various states, provinces, and even some countries in Europe. And even if such a change doesn’t occur in Washington, similar opportunities for regulatory reform exist in states and cities throughout the country.

Yandle’s Reading Table

Arthur C. Brooks’s latest book is a personal story about how one might find more happiness in life’s second half. From Strength to Strength: Finding Success, Happiness, and Deep Purpose in the Second Half of Life begins when Brooks hears an elderly man say to his wife that he has nothing to live for. The conversation continues, and Brooks later recognizes the man as a renowned public figure, one who had lived productively but now, after having always strived to achieve success and recognition, is no longer engaged with the world. His life seems to have lost its meaning. As Brooks later emphasizes, life for strivers can seem awfully empty when there is nothing left to strive for.

As Brooks is listening to the conversation and thinking, he is typing away on his laptop, knowing that he cannot waste a minute in completing a piece to satisfy a Washington deadline. At the time, with a PhD in economics, he was president of American Enterprise Institute, a hard-hitting Washington public policy think tank; he was a successful best-seller writer, and he was prosperous. And of course, he would not have accomplished so much were he not a striver. But unlike the elderly man, Brooks is not elderly or even thinking about retirement. These thoughts inspire the book.

For the book to work, Brooks must convince high-striving readers that their days of roaring success are numbered and that the frequency of celebration picnics and high fives will peak out long before they themselves are ready to pull out porch rockers and relax. If persuaded, the reader must then focus on the second half of life, think about reordering priorities and discovering important new meaningful things to aspire to.

To get his story underway, Brooks provides a survey of studies and experiences that focus on the life cycle of success and the question, when do most people hit peak performance in their careers and find declining prospects from that point forward? His survey finds that for many professions and fields of activity, performance peaks after about 20 years of work. Whether it be musicians, lawyers, or scientists, the data show that those who strive successfully and perform well will find themselves joining the ranks of the restless low performers when they hit age 50 or so. They will begin to be celebrated for what they were, not what they are.

Of course, there are outliers, and each one of us, dear reader, probably thinks that none of this really applies, that we are exceptional. Self-delusion does tend to occur, doesn’t it? But if we accept the data and the author’s analysis, we are left with two possibilities. We can expect and prepare for declining years of productivity and lower levels of happiness, or we can grab the bull by the horns and decide to change what we do, how we live, and what’s worth striving for, and we can live differently.

In his second chapter, Brooks introduces the work of Raymond Cattell, who argued that there are two kinds of intelligence: One, which he termed fluid, draws on one’s native ability to reason—what some call raw smarts. Researchers point out that this form of intelligence is powerful for young people but declines with age. The second type is crystallized intelligence, which forms from experience, from specialized learning, and from dealing with the ups and downs of life. Fluid intelligence, high during younger years but declining, can be supplemented with or countered by crystallized intelligence, which grows even into maturity and old age. The formation that results can enable the maturing person to experience a renewed mind that will support a different way of life in the senior years.

Along with this agreeable idea, the author discusses the lives and contributions of J. S. Bach and Cicero, emphasizing that the magnificence of their work propelled them forward for years but, in Bach’s case, was overshadowed by new styles of music composed by such people as his own son, C. P. E. Bach. But the elder Bach did not fret away his life. Instead, he became a master teacher and author of books describing music fundamentals that inspired others. He found a new purpose to strive for in the second half of his life.

With chapter titles such as “Kick your Success Addiction,” “Ponder Your Death,” and “Cast into the Falling Tide,” Brooks provides plenty for the reader to think about and react to when contemplating if they will find a new life after 65. The fact that Brooks himself follows the prescription of the book makes his answer to this question all the more credible. In closing the story, the author returns to the opening story, his eavesdropping on a man telling his wife that life no longer had meaning. Brooks expresses deep appreciation to this anonymous person for having helped to open his eyes about living differently so that the second half of his life would have greater meaning. The author summarizes his learning in seven words: “use things”; “love people”; “worship the divine.” Pointer: play with rearranging the verbs to contrast these commandments with common values in society; this exercise and the resulting contrasts will help elucidate Brooks’ pursuit of meaning.

Martin Gurri’s The Revolt of the Public and the Crisis of Authority in the New Millennium focuses on the explosive growth of almost costless communication by way of social media. In laying out the implications, the author provides a fascinating account of how the rise of social media has done far more than just lower the transaction costs of political and collective decision-making. Instead of just bringing down communication costs within an existing set of institutional arrangements, burgeoning social media have displaced and replaced older communicating media and the dominant talking heads that interpreted news for the masses.

Using such platforms as Facebook and Twitter has made it possible for members of the public to step around the political middlemen and, by way of revolution or threats of same, bring about major change and quickly.

Gurri refers to this major revolution in how people communicate as the Fifth Wave. The first four waves, which were revolutionary in their time, were (1) the invention of writing, (2) the development of alphabets, (3) the invention of moveable type and the printing press, and (4) the rise of mass media. As Gurri sees it, the Fifth Wave’s implications for new world order are profound.

Using social media merely to more effectively get out the vote and find fresh talent would be one thing. But as Gurri argues, the changes are not just transactional; they are tectonic. As he sees it, people are witnessing a new game, not simply a more effective old one. And the new game means that the public—all of those who think of themselves as citizens or members of the same tribe—can suddenly be inspired by a distressed peasant who torches himself or by a female athlete who refuses to wear a religion-dictated item of clothing; and through instant smart phone communication they can create chaos and bring about political change. In America, according to the author, we, the public, are more engaged in doing things our way. And our way is generally not the way that may have been chosen in the past by media and other elites who played the role of tastemakers and matchmakers in American politics.

Americans saw an early precursor to this when, by making extraordinary use of social media data, Barack Obama, a relatively unknown Illinois state senator, achieved national prominence in rapid time and became president. To top this, we have seen how a highly successful TV personality and global operator of hotels, casinos, and even beauty pageants, Donald Trump, never having held elected office, became president of the United States. And then, following his unsuccessful effort to win a second term, his disappointed base used social media to organize an assault on Congress and disrupt the constitutional process for naming a newly elected president.

Yes, as Gurri points out, the rise of social media has made Twitter and Facebook more important for conveying political thought and messages than the major news networks and certainly the already rapidly disappearing daily newspapers. Indeed, before having his personal account suspended in 2021 by Twitter because of his inflammatory messages, President Trump had 88.9 million Twitter followers and had posted 25,000 messages during his presidency. As NPR’s Tamara Keith put it in 2016, “An unprecedented feature of Donald Trump’s successful campaign for president was his personal use of Twitter and it has continued as Trump meets with advisers and potential members of his cabinet. If this continues into Trump’s presidency, the method will be new, but the approach will be in line with a long tradition of presidents going around the so-called filter of the press.”

To a meaningful extent, the Fifth Wave was powered by Twitter and other social media, which amplified the rising level of public distrust of standing political hierarchies. One will soon learn whether Elon Musk will make good of his promise to effect major changes to Twitter.

Chapter five in Gurri’s stimulating book, titled “Phase Change 2011,” describes 2011 as the tipping point when public distrust of government across the world caused people to take to the streets and demand change. The chapter focuses on how people became mobilized for “real democracy” and, as Gurri puts it, “denied that their elected representatives represented them.” Along with other similar stories, the author gives a Fifth Wave explanation of the 2011 indignados, or “the outraged,” movement in Spain. Growing out of the deep 2008 recession, which led to 45 percent unemployment, the movement did not focus on the economy, according to the author, but instead attacked the entire political class, the “ruling” elite who had made promises without delivering. Gurri describes the situation: “The view from below, in Spain, in the troubled year 2011, fixated on the people at the top, on the ruling elites, on their empty claims, on what seemed like the decisive failure of established institutions to deliver on the social contract . . . . The breach of trust, for many, extended well beyond any one party or policy to a ‘partycratic dictatorship’ stuck in fossilized immobility."

With chapter titles like “A Crisis of Authority,” “The Failure of Government,” and “Choices and Systems,” Gurri builds a case for the revolt of the public and the arrival of a different era of governance. But while this story is fascinating and, I think, worthy of consideration and discussion, the author reminds readers that his arguments are tentative. Yet at the same time, in his introduction, the author also reminds readers that “it’s early days. The transformation has barely begun, and resistance to the old order will make the consequence nonlinear, uncertain . . . . Welcome, friend, to the Fifth Wave."