- | Monetary Policy Monetary Policy

- | Policy Briefs Policy Briefs

- |

Do Price Controls Work? Lessons from Hyperinflations under Dictatorial Regimes

People in different households tend to consume different baskets of goods, and the prices people pay for the same goods may differ across transactions, so people may experience inflation differently. But one thing is clear: people do not like to pay higher prices when they experience inflation. When the rate of inflation rises to a point that concerns voters, elected officials may be tempted to use price controls—measures that dictate the maximum price merchants can charge customers for goods. Can price ceilings stop inflation? The United States’ experience suggests not really. But what if the checks and balances officials in the United States face hamper efforts to fully implement mandated maximum prices? Then it is useful to examine how price controls have worked under more dictatorial regimes that resort to violence to enforce mandated maximum prices during hyperinflation.

As in the United States, the recent experiences in Zimbabwe and Venezuela as well as in Revolutionary France (the first hyperinflation ever recorded) suggest that attempts to prevent prices from rising above a ceiling during a hyperinflationary episode create shortages. Such shortages spur illegal black-market transactions, where prices can escalate much higher because they are not subjected to the price controls. Therefore, even in more dictatorial regimes, the evidence suggests that price controls do little to limit the rate of inflation.

In this policy brief, I will define hyperinflation, summarize the historical record of hyperinflations, and then discuss the ineffective use of exchange and price controls during the most recent hyperinflations in Zimbabwe, Venezuela, and Revolutionary France.

What Are Hyperinflations? How Many Have There Been?

Hyperinflations arise when government funds large deficits by printing currency. While the definition is somewhat arbitrary, a hyperinflationary episode begins when inflation, the growth rate of the general price level, equals at least 50 percent in a given month. And it ends when the rate of inflation does not exceed 50 percent during the ensuing 12 months. Based on available data, history suggests that Revolutionary France experienced the first recorded episode in 1793, and it experienced another from 1795 to 1797; almost all other episodes have occurred from the beginning of the 20th century to the present, with Venezuela and Zimbabwe experiencing the most recent episodes. In total, there have been at least 31 hyperinflationary episodes, and possibly close to 60 if one includes the former USSR countries after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

Urban Consumers and Official Controls in Developing Economies

Governments in countries experiencing hyperinflation face challenges collecting enough revenue from taxes or debt to fund expenditures, so they often compensate for revenue shortfalls by printing currency. As the value of the domestic currency declines rapidly, officials may also turn to exchange controls to limit people’s ability to trade in foreign currencies for domestic use in an effort to keep the domestic currency valued higher than in the domestic black or parallel markets. Exchange controls tend to make exports of agricultural products and fuel expensive, and they tend to make imports of agricultural products and fuel cheap.

Furthermore, officials in developing countries often must seek to appease urban consumers by keeping food and fuel prices low. If a country has a monopsony crop marketing board (sole buyer) as part of its colonial legacy, such a board tends to buy crops domestically at low prices from rural farmers, which discourages production of those crops. Therefore, officials may turn to exchange controls to ensure that imported items remain relatively cheap and price controls to further ensure that urban consumers pay low prices. However, during hyperinflation, exchange controls prove ineffective as black markets for foreign currency emerge to help people deal with the loss of purchasing power with domestic currency. Price controls also prove ineffective, as they tend to result in shortages in the formal sectors and spur informal sector exchanges where prices track the hyperinflation.

I discuss the Zimbabwean, Venezuelan, and Revolutionary French experiences with price controls during hyperinflation next.

Zimbabwe’s Hyperinflations and Price Controls

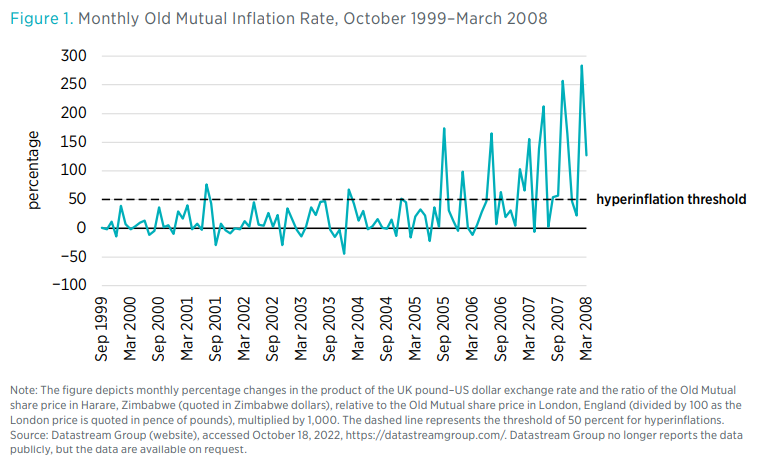

Figure 1 shows the monthly inflation rate in Zimbabwe computed using the Old Mutual rate from October 1999 to March 2008. The data suggest that Zimbabwe experienced two hyperinflationary episodes during this time. The first occurred in July 2001 and the second from January 2004—just after former Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) Governor Gideon Gono, who was widely viewed as the architect behind the latter hyperinflation, took office—to the end of March 2008.

As is typical during hyperinflations, as the RBZ printed more currency, Governor Gono blamed speculators for the hyperinflation and even attempted to shut down the stock market to prevent people from finding out about the Old Mutual inflation rate. The hyperinflation ended in 2009, when the government officially dollarized and allowed people to transact and pay taxes in foreign currency. However, since the official dollarization ended in 2019, the Zimbabwean economy has once again been experiencing renewed hyperinflationary pressures.

Before the hyperinflation unfolded, the government in Zimbabwe periodically used price controls for politically favored goods (as discussed in the previous section), which the International Monetary Fund (IMF) recommended dropping. However, after the first hyperinflationary episode in mid-2001, officials implemented price controls on maize and wheat and eventually other goods. By late 2002, roughly 70 percent of the goods in the consumer price index were subjected to price controls, but nonetheless merchant shelves emptied and goods trade moved to the black market.

After Governor Gono took office in December 2003, the rate of inflation began to increase again, with the second hyperinflation beginning in January 2004. By 2007, with officials unable to control the rate of inflation, the government again began to implement price controls, called “Operation Dzikisai Mitengo/Slash Prices.” However, the operation spurred more black-market activity, and the government eventually resorted to using police officers, soldiers, and members of the youth militia to intimidate merchants to keep prices in check. But to no avail. What ultimately ended the hyperinflation was the RBZ’s inability to acquire new note paper followed by an official dollarization, not price controls.

Venezuela’s Hyperinflation and Price Controls

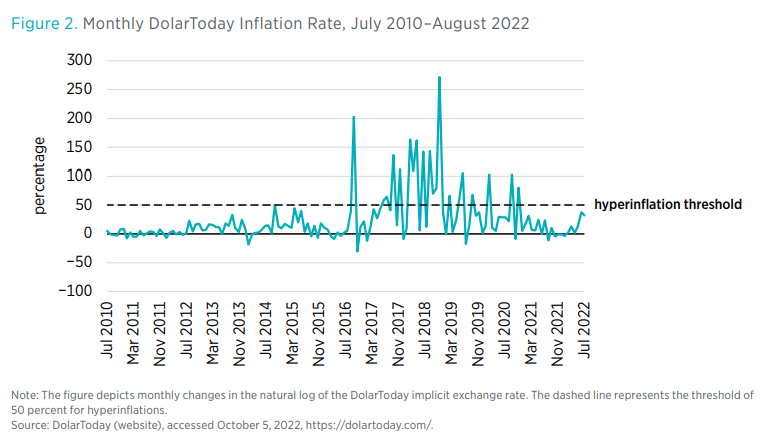

Figure 2 shows the monthly inflation rate in Venezuela, computed using the DolarToday index from July 2010 to August 2022. The data show that the hyperinflation began in November 2016 and ended in January 2022, although inflation still remains high. Much like in Zimbabwe, Venezuela’s socialist Bolivarian Revolution (1999–present) has made extensive use of exchange controls to prevent the currency from losing value and price controls to keep staple goods prices low. Also like in Zimbabwe, exchange controls spurred black-market foreign-currency transactions while price controls spurred formal-sector shortages and black-market goods transactions where prices reflect the ongoing inflation. The government began allowing unofficial dollarization in 2019, so people could undertake transactions in foreign currencies. The inflation rate began falling after that, but in recent months it has increased.

Revolutionary France’s Hyperinflation and Price Controls

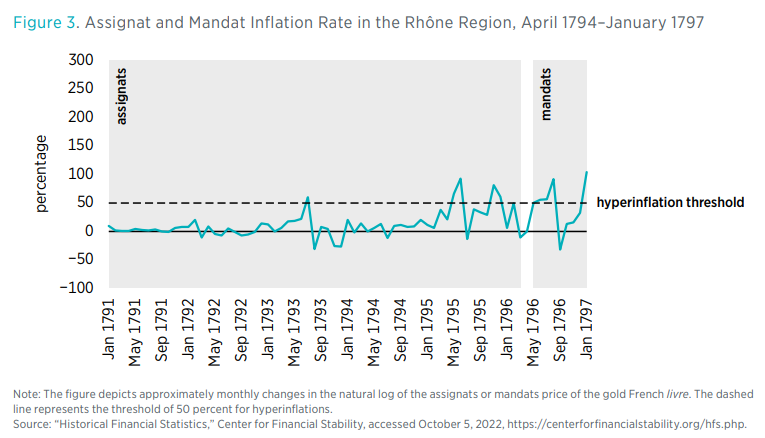

Figure 3 shows the monthly inflation rate in Revolutionary France from January 1791 to March 1796 for the assignats and from May 1796 to January 1797 for the mandats. The mid-month price index for the Rhône region is used to measure inflation.

The assignats emerged in December 1789, when the National Assembly created a paper currency partially backed by the eventual sale of expropriated Church-owned land. However, people lost confidence in the currency by 1792 as inflation increased, which spurred a search for new lands to expropriate. By May 1793, the regime introduced the first maximum, which served as a price control on grain to stem inflation. But the first bout of hyperinflation occurred in July 1793. Despite inspections to certify the amount of grain produced, shortages arose, as did people’s attempts to use foreign currencies to make purchases. The regime, therefore, introduced a broader set of price and exchange controls, called the “Law of the General Maximum.” Under Maximilien de Robespierre’s Reign of Terror, between August 1793 and July 1794, people were forced to use 1790 prices for goods and assignats rather than foreign currencies or gold and silver. But, ultimately, the Terror failed, and the price controls were thought to be the reason behind the ongoing food shortages.

As inflation continued to rise, and with the second bout of hyperinflation beginning in May 1795, the regime placed a cap on the amount of assignats that could be issued in December 1795, which was reached couple of months later in February 1796. The regime then introduced the mandats in March 1796. Their issuance was capped at 2.4 billion, half of which was used up in converting outstanding assignats at a 30 to 1 rate. But this, too, did not last, and the regime abandoned the mandats and allowed the return of gold and silver.

Conclusion

The similarities abound between the two most recent hyperinflations in Zimbabwe and Venezuela and the first ever recorded episode in Revolutionary France. These episodes begin with the governments turning to the printing presses to fund deficits. People then attempt to use foreign currencies or gold and silver, which have more purchasing power than the domestic currency, to compensate for the hyperinflationary pressures. The governments in turn use exchange controls to prevent such actions, which increase the official value of the currency relative to what it is in black markets, making domestic goods relatively expensive and foreign goods relatively cheap. Therefore, governments impose price controls along with exchange controls to force people to exchange domestic currency for goods at lower prices. But, inevitably, exchange and price controls cannot eliminate the inflationary pressure—only currency and fiscal reform can fix hyperinflation.